Chapter X

Barely surviving the first winter

Many die of disease; harsh weather and fire

severely disrupt construction; then in the spring,

at last, comes the first friendly Indian welcome.

There also had been some happy moments aboard the Mayflower while

the shallop was away on the third exploratory trip. Mourt's

Relation recorded how "it pleased God that Mistress White

was brought to bed of a son, which was called Peregrine." Susanna

White's new son, whose older brother was born in Leyden, was the

first English child born in New England.

But mostly, the waiting, anxious hours for the Mayflower passengers

were not happy ones.

The death of Dorothy Bradford was followed the next day by the

death of a victim of the General Sickness, a 57-year-old tailor

recruited by the London adventurers. Many aboard were sick. The

number of passengers would be steadily diminished. Within a few

weeks, the sickness would take the lives of both Peregrine's father

and the tailor's wife.

Indeed, when the passengers set about discussing where they should

dwell, they had already dug four graves. A memorial to these first

victims, whose adventure into the New World in search of religious

freedom and a new life had come so quickly to an end, may be seen

today in the center of Provincetown. And soon for the dwindling

band of pioneers there would be many, many more untimely graves.

On Dec. 15, Master Jones weighed anchor and the Mayflower left

future Provincetown Harbor. When the ship came within six miles

of Plymouth Bay, the head winds made it impossible "to fetch the

harbor," and they went back. With a fair wind the next day the

Pilgrims put to sea again, and managed to reach the harbor safely

just before the winds shifted.

Jones dropped anchor just inside Beach Point, the northern tip

of the three-mile-long spit of land, now called Plymouth Beach,

that forms the eastern barrier and a natural breakwater for Plymouth

Harbor. The Mayflower was "a mile and almost

a half" from the granite boulder later christened Plymouth Rock--an

almost solitary, glacier-age deposit on this part of the sandy

and shallow shore.

The Pilgrims had arrived on Saturday--a time for preparing food,

attire and furnishings for the coming Sabbath that, regardless

of loss of time, they persisted in observing as an occasion for

religion and rest.

Still, the Pilgrims noted from shipboard that the harbor was "a

bay greater than Cape Cod" and "compassed with goodly land." Stretching

from their anchorage toward future Kingston and Duxbury, the bay

seemed to them "in fashion like a cycle or fishhook."

No one went ashore until Monday, Dec. 18. On that morning members

of the company began explorations to decide exactly where they

should begin building. The search would consume three days.

For hours they marched along the coast, and went seven or eight

miles through the woods without seeing any Indians. They examined

land formerly planted by the Indians, its soil good to the depth

of a spade's blade. They found a great variety of familiar trees

and vines, "and many others which we know not." They found brooks

and springs, and praised the water as "the best...that ever we

drunk." Weary from marching, they went back that night to the Mayflower.

Some by land and some in the shallop pressed their search the

next day.

The shallop went three miles up a creek in the future town of

Kingston, and the explorers named it the Jones River after the Mayflower's captain.

The group also crossed the bay to examine Clarks Island.

On returning that night to the Mayflower, they resolved that next

day they would "settle on some of those places" they had just

seen.

In the morning they "called on God for direction" and went for "a

better view" of just two of the places previously explored.

Clarks Island was excluded as too small. They felt keenly the

need to save time, "our victuals being much spent, especially

our beer." [This isn't like it sounds, "we're in trouble, the

beer's running out!" Beer for them was safer than the potable

water they had on board. The sooner they could settle next to

those brooks and streams, the better, was the message here.] And

so, immediately after an additional look, they voted for the high

ground they had inspected the first day--the land back of the

great rock.

Here there was everything they sought. As they reported: "There

is a great deal of land cleared, and hath been planted with corn

three or four years ago; and there is a very sweet brook runs

under the hill side, and many delicate springs...and where we

may harbor our shallops and boats exceedingly well; and in this

brook much good fish in their seasons; on the further side of

the river also much corn-ground cleared. In one field is a great

hill, on which we point to make a platform, and plant our ordnance..."

Thus, before names had been bestowed upon them, the Pilgrims were

describing Cole's Hill, directly back of Plymouth Rock; Town Brook

on the hill's south side; Pilgrim Spring, still flowing in Brewster

Garden; and 165 feet above the sea, Burial Hill, on which they

would build a fort-meetinghouse--a hill from which they could

that day "see thence Cape Cod."

Twenty decided to spend the night right there, while those returning

to the Mayflower promised to be back in the morning to

start building houses. But harsh December weather interfered.

That night there was a tempest of pelting rain and strong winds.

Those ashore had had insufficient daylight to build an adequate

shelter and were soaked. They "had no victuals on land" and the

winds blew so fiercely that the shallop could not return. On the Mayflower,

meanwhile, it was necessary to "ride with three anchors ahead."

The gale made travel next day between ship and shore impossible.

It was on this day the Mary, wife of Isaac Allerton, gave birth

to a stillborn son. Mary Allerton, mother of three children born

in Leyden, would herself die in a few weeks.

Preparations for building did get under way on Saturday, Dec.

23, with as many as were able joining those ashore. First, though,

they had to dig two graves: one for the Allerton infant and another

for a youth from London who had died on shipboard the first day

of the storm.

On Saturday and the following days, even on Christmas Day,

they kept busy: "Some to fell timber, some to saw, some to rive

(split), and some to carry; so no man rested all that day." Bradford,

moreover, wrote that it was on Christmas Day that they "began

to erect the first house for common use to receive them and their

goods." The common house was atop Cole's Hill, on its south

side, and near the foot of modern Leyden street, the first street

in New England.

That Christmas Night on the Mayflower, Jones provided "some

beer, but on shore none at all."

[The Pilgrims didn't believe in celebrating Christmas, probably

due to it's being observed on the day of the old Roman Saturnalia

observance, and that the Scripture nowhere mentions the command

to observe the Lord's birthday. They were striving with all their

might for the faith once delivered, and none of the later

additions to the faith that came centuries later which weren't

a part of the Bible.]

Foul weather occurred most days during the remainder of December,

leaving the people ashore "much troubled and discouraged".

On Dec. 28 the Pilgrims made a very practical decision, after

concluding that "two rows of houses and a fair street" along with

a platform for ordnance on the hilltop would be "easier impaled." The

decision was to have single men without wives join families "so

we might build fewer houses." Then lots were cast for 19 "household

units."

The Pilgrims were already talking about the "weakness of our people." They

recorded that many were "growing ill with colds; for our former

discoveries in frost and storms, and the wading at Cape Cod had

brought much weakness amongst us, which increased so every day

more and more." By December's end six had died. In January eight

more would follow them, and still the agony and the dreadful toll

of the General Sickness would grow.

Keen as the Pilgrims were to become acquainted with their Indian

neighbors, they worried that the reduction in their number might

invite attack. To conceal their losses, they resorted to burials

in unmarked graves on Cole's Hill.

Those doing the building saw, at a distance they judged to be

six or seven miles, smoke from Indian fires. And on Jan. 3 some

who had gone to gather thatch "saw great fires of the Indians."

A group went to the former cornfields, but saw no Indians. The

next day Myles Standish and four or five others sought to meet

the Indians. They found Indian dwellings, "not lately inhabited"--but

again, no Indians. As the 20-foot-square common house neared completion,

with about eight days more needed to finish the thatching, the

Pilgrims on Jan. 9 decided on a new plan for building their small

houses. That day they divided the meersteads (acreage) and garden

plots "after the proportion formerly allotted," and agreed that

"every man should build his own house, thinking by that course

men would make more haste than working in common."

This sort of private initiative was a principle in which the Pilgrims,

close-knit though they were in fellowship, deeply believed. Allegiance

to it was why they had refused, when leaving Southampton, to accede

to the harsh demands of Thomas Weston and the London adventurers.

They would adhere to this principle in the future in other crucial

decisions about developing their plantation. [The real birth of

our Free Enterprise system was taking place right here.]

The January weather was so foul that they found that "seldom could

we work half the week."

Pilgrims aboard the Mayflower were up early Sunday, Jan. 14, to

go to join those on land--by then the larger group--for their

first Sabbath meeting ashore. The wind was blowing strongly, and

as they looked toward Leyden street they suddenly "espied their

great new rendezvous (common house) on fire." A spark had landed

in the thatch and fire was rapidly spreading.

While at work three days earlier, Bradford had been stricken with

such pain in his hip and legs that there was fear he would die.

He already had a severe cold. When the thatch flared up he and

Gov. Carver lay sick in bed in the common house. Near them were

gunpowder and charged muskets.

"Through God's mercy they had no harm," reported Mourt's Relation.

The fire consumed only the thatch. The roof still stood, but some

who had transferred ashore had to resume quarters aboard the Mayflower.

The common house, in any case, had not provided adequate quarters.

It had been "as full of beds as they could lie one by another." So,

besides repairing the roof, the Pilgrims spent two days building

a shed "to put our common provision in."

They did get to hold their first Sabbath meeting ashore the following

Sunday, Jan. 21.

THE REST OF THE MONTH,

WHEN

"FROSTY weather and sleet" would let them, the Pilgrims used the

shallop and longboat to bring ashore common provisions, like hogsheads

of meal. These they carried up to storage.

The manifold tasks facing them were made more arduous by illness,

on shipboard and shore, and by the steady decline in their numbers.

"The sickness," said Bradford, "began to fall sore amongst them" after

the fire. February would bring their greatest loss of life, with

sometimes two or three being buried in a single night. In all,

seventeen more passengers would perish by the end of the month,

and one of the small houses--briefly endangered when a spark kindled

the roof--had to be pressed into use to help care for the increased

number of the sick.

The February weather, after starting "with the greatest gusts

of wind that ever we had since we came forth," continued mostly

severe. The Mayflower, lightened now because of goods

that had been brought ashore, was "in danger."

Often the weather made work impossible. And by mid-month the Pilgrims

became deeply concerned about their security.

On Feb. 16, a fair day, one of the Pilgrims went fowling in the

reeds about a mile-and-a-half from the plantation. Suddenly he

saw a dozen Indians headed toward the plantation, and could hear

in the woods "the noise of many more." He laid low, then ran home

to give the alarm.

That same day Myles Standish and a companion left their tools

in the woods and, on returning, found that the Indians had taken

them.

Muskets that had been allowed to get out of temper--firing condition--because

of moisture were promptly put in order, and a strict watch was

set. The next day, the Pilgrims assembled to establish "military

orders among ourselves." Standish was formally elected captain

and was voted full authority to command in military affairs.

Even as they were engaged in this activity, there appeared two

Indians atop Watson's Hill (the Pilgrims called it Strawberry

Hill), which was then much higher than it is today and was to

the south of the plantation, immediately across from Town Brook.

Standish and Stephen Hopkins hurried across the brook and laid

down a musket to show their desire to parley. The Indians--including

some who had been concealed behind the hill--abruptly took off.

The sudden appearance of so many Indians caused the puzzled Pilgrims

to begin getting their ordnance in place.

Jones, with some crewmen, brought ashore a minion--a cannon with

a 3 1/2-inch bore. This, along with a larger bore cannon called

a saker that had been left by the shore, were lugged to the platform

on top of Burial Hill. They were mounted there with two smaller

cannon, called bases, which had a 1 1/2-inch bore. The work was

completed Feb. 21--the same day four passengers died, among them

the father of Peregrine White.

During March the General Sickness would claim thirteen more lives.

Still, it was during this month that the Pilgrims would for the

first time hear thunder and the songs of birds in New England,

and would sow some garden seeds--true signs, all of them, of springtime

and renewed hope.

"The spring now approaching," said Bradford, "it pleased God the

mortality began to cease amongst them, and the sick and the lame

recovered apace, which put as it were new life into them, and

contentedness as I think any people could do. But it was the Lord

which upheld them..."

When the General Sickness had finally run its course, half

of all Mayflower's passengers had perished.

The loss among the wives was the heaviest. Among the eighteen

couples aboard, eight of the men but only four of the women

survived. Four families were wiped out, and only in three families

did all the members survive. Six children lost one parent and

five lost both.

Children fared comparatively well, with twenty-five of thirty-two

surviving. Of the eleven young women, only one died. Among the

nine male servants, the toll was appalling: All but one perished.

There were two doctors in the company: the Mayflower's doctor,

Giles Heale, and Samuel Fuller, a weaver while in Leyden who functioned

as the Pilgrims'

"surgeon and physician." Fuller, said Bradford, was a tender-hearted

man and "a great help and comfort to them." During the General

Sickness, however, neither doctor was mentioned. Perhaps they,

like Bradford, were among those stricken.

Accounts are far from specific as to the name or proper treatment

for the dreadful sickness. Medical techniques of that day were

so primitive that they could have brought more harm than cure

to patients unquestionably suffering from improper diet, anxiety,

overexertion, and exposure to damp and cold. Bradford ascribed

the affliction to "the scurvy and other diseases which this long

voyage and their inaccomodate condition had brought upon them." The

other diseases could have been pneumonia or ship fever, a form

of typhus.

Jones' crew did not escape. "Almost half of their company died before

they went away," said Bradford, "many of their officers and lustiest

men, as the boatswain, gunner, three quartermasters, the cook

and others." Neither the names of the crew, beyond a few, nor

their exact number have come down to us. But their estimated loss

of life must be added to the steep figure we have of passenger

deaths.

Bradford also told of the

"rare example" shown during the General Sickness by the seven

Pilgrims who escaped affliction. These, he said, "spared no

pains night nor day, but with abundance of toil and hazard of

their own health, fetched them (the sick) wood, made them fires,

dressed their meat, made their beds, washed their loathesome

clothes, clothed and unclothed them. In a word, did all the

homely and necessary offices for them which dainty and queasy

stomachs cannot endure to hear named...

"Two of these seven were Mr. William Brewster, their Reverend

Elder, and Myles Standish, their Captain and military commander,

unto whom myself and many others were much beholden in our low

and sick condition."

Since coming to the New World, all of the future leaders of Plymouth

except Brewster had been widowed--Bradford by an accident, Winslow

and Standish by the General Sickness.

From Leyden their beloved pastor, Rev. John Robinson, wrote in

June: "The death of so many of our dear friends and brethren,

oh! Oh how grievous hath it been..." But he still was confident

that God's mercy could be seen in the fact that He had spared

so many of their leaders, and that He would ensure victory in

their struggle to provide "godly and wise government."

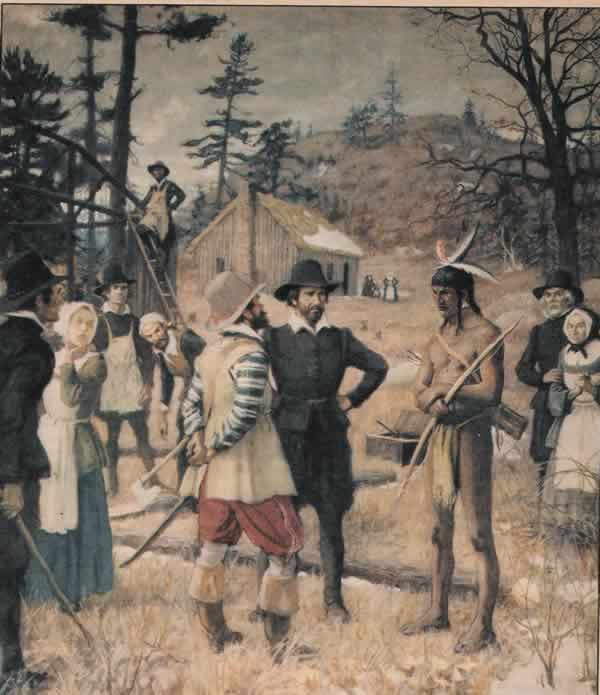

Mid-March, at last brought the beautiful greeting that the Pilgrims

had yearned to hear ever since they first caught sight of the

New England coast.

On March 16 Standish and the other men--now fewer than two dozen--were

interrupted as they sought to complete discussion of their new

military organization. A tall, straight Indian, "stark naked,

only a leather about his waist," carrying a bow and two arrows,

cause an alarm as he approached the common house.

"He very boldly came all alone, and along the houses, straight

to the rendezvous...He saluted us in English, and bade us, 'Welcome!'"

Samoset Welcoming Pilgrims