Chapter IV

At long last, freedom in Holland

Out of jail, the Pilgrims survive a fierce storm

and official abuse to reach their haven, but soon

confront another problem: poverty amidst plenty.

Bradford did not mention that

the Puritan leanings of the Boston magistrates aroused their compassion

for the Pilgrim men, women and children confined in the coastal

town after their betrayal by a devious shipmaster. But the comparative

leniency of the Bostonians--many undoubtedly members of the St.

Botolph's Church--is certainly its own eloquent testimony.

The magistrates, said Bradford, treated the Pilgrims "courteously,

and showed them what favor they could: but could not deliver (free)

them till an order came from the (Privy) Council table" in London;

this took some weeks. The order's moderation when it did arrive

implies that the magistrates may have minimized the charges brought

against the Pilgrims.

In his summation, Bradford said, "After a month's imprisonment,

the greatest part were dismissed; and sent to places from whence

they came: but seven of the principals were still kept in the prison,

and bound over to the assizes (court)."

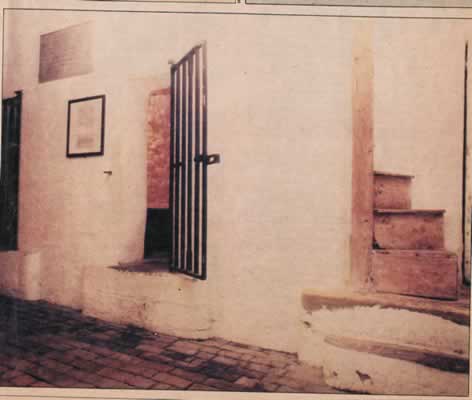

The cells where the Pilgrims would have been held--still to be seen--comprised

the town jail in the old Guildhall. They have heavily barred doors

and are windowless. A winding flight of stone steps leads up, through

a trapdoor, to the courtroom.

The name of only one of the seven imprisoned leaders has come down

specifically: William Brewster. The assize inquest

led to no action, and Brewster and the others were finally released.

No one knows how the Pilgrims, having been stripped of their money,

were afterwards able to provide for themselves, though their friends

and former neighbors must have helped.

In any case, by the winter and spring of 1608 new arrangements were

being made for an escape to Holland. There was added urgency, for

agents of the ecclesiastical authorities had been moving against

the Pilgrims. One, the grandson of Nottinghamshire's high sheriff,

had been charged, on Nov. 10, 1607, as "a very dangerous, schismatical

Separatist, Brownist, and irreligious subject, holding and maintaining

divers erroneous opinions." For his "unreverent, contemptuous

& scandalous speeches" to the court, he was immured in the castle

at York.

And on Dec. 1, 1607, William Brewster and another member of the

congregation were charged with being "disobedient in matters of

religion."

Neither appeared in court but each was fined 20 pounds (then half

a year's pay) and attachments were ordered. [This gives a little

insight into the value of the pound in the 1600's. For a person

at the lower end of the scale like these farmers, $17,500 could

be half a years wages in today's wages. Imagine being fined that?

The British pound was worth $5.00US in the mid 1800's.]

Two weeks later, on Dec. 15, the court's agent "certified that he

can not find them (Brewster and his co-defendant), nor understand

where they are." A peek into the Guildhall's municipal cells in

Boston might have given him the answer.

Once more the Pilgrims were preparing to leave Scrooby, but this

time we know something of the way they went to meet the Dutch shipmaster

who would take them aboard ship on the coast between Grimsby and

Hull--then and now great fishing ports on either side of the Humber

River, an estuary of the North Sea between Yorkshire and Lincolnshire.

The boarding place, unnamed seemed secure, for it was in a remote

location on the flat, marshy coast, "where was a large common a

good way distant from any town."

The Dutch shipmaster owned his vessel. The Pilgrims who made the

arrangements had chanced upon him in Hull on the northern, Yorkshire

side of the Humber. "They made agreement with him, and acquainted

him with their condition, hoping to find more faithfulness in him

than in the former (shipmaster) of their own nation. He bade them

not fear, for he would do well enough." And he did.

Scrooby is in the broad valley of the Trent River, which loops nearly

200 miles across the English Midlands. The Ryton River, a short

distance north of Scrooby, joins another small waterway, the Idle

River, which in turn flows into the Trent.

The Pilgrim men placed the women, children and belongings into boats

on the Ryton and, on reaching the Trent, transferred them into "a

small bark which they had hired." Then those men not needed to manage

the bark walked 30 miles across northern Lincolnshire to the isolated "large

common."

The bark sailed northward on the Trent to where Yorkshire's Ouse

River comes down from the north, and together with the Trent forms

the Humber River, flowing eastward to the sea. The common was on

the south side of the broad estuary of the Humber where it enters

the North Sea, just above Grimsby.

The tides in the estuary are fast and forceful. The passage was

rough, and when the women became seasick they "prevailed on the

seamen to put into a creek hard by where they lay on the ground

at low water."

Their arrival at what is now generally believed to have been Immingham

Creek, five miles north of Grimsby, was a day early.

Next day, when the Dutch shipmaster arrived offshore, "they were

fast (aground) and could not stir until about noon." Meantime the

shipmaster, seeing the men "walking about the shore,"

decided to save time and sent a boat to fetch them on board. He

was ready to send for another boatload, said Bradford, who was among

those already aboard the ship, when:

"The master espied a great company, both horse and foot, with bills

(a long-handled weapon with a hooked blade) and guns and other weapons,

for the country (local area) was raised against them. The Dutchman,

seeing that, swore his country's oath, 'Sacrement!', and having

wind fair, weighed his anchor, hoisted sails, and away." Which was

about all he could sensibly do.

Spies, bounty seekers, must have alerted the sheriff, constables

and catchpolls.

The men most sought by the authorities--including Brewster and the

Pilgrims' two Separatist clergymen--fled into the countryside. Bradford

said that the Pilgrim men "made shift to escape before the troops

could surprise them, those only staying that best might be assistant

unto the women.

"Pitiful it was to see the heavy case of these poor women in this

distress; what weeping and crying on every side, some for their

husbands that were carried away in the ship...others not knowing

what should become of them and their little ones; others again melted

in tears, seeing their poor little ones hanging about them, crying

for fear and quaking with cold."

On the ship, said Bradford, "the poor men were in great distress

for their wives and children which they saw thus to be taken, and

were left destitute of their helps; and themselves also, not having

a cloth to shift (reclothe) them with, more than they had on their

backs, and some scarce a penny about them, all they had being aboard

the bark.

"It drew tears from their eyes, and anything they had they would have given

to have been ashore again, but all in vain, there was no remedy, they must

thus sadly part."

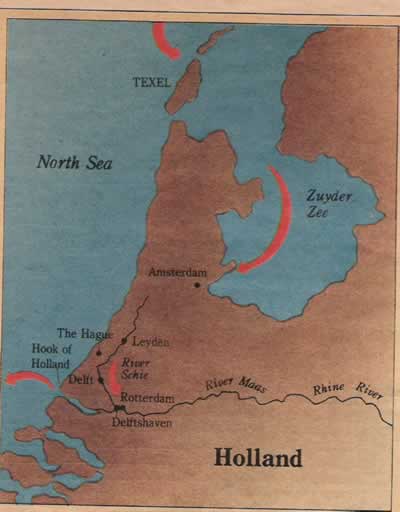

Normally, it is about 200 miles across the North Sea to the narrow

entrance past Texel Island into the Old Zuider Zee (South Sea);

and thence some 50 miles south down this great gulf to Amsterdam--which

at that time, despite the war with mighty Spain, was the thriving

commercial heart of the most advanced and prosperous nation in Europe.

But that is not how the trip to Holland went for these profoundly

distressed men.

En route, there arose "a fearful storm at sea" and the ship was

driven near the coast of Norway 400 miles to the north. The passage

consumed two weeks more, and half of that time the Pilgrims "neither

saw sun, moon nor stars...the mariners themselves often despairing

of life, and once with shrieks and cries gave over all, as if the

ship had been foundered in the sea and they sinking without recovery.

"When the water ran into their mouths and ears and the mariners cried out, "We

sink, we sink!" they (the Pilgrims) cried, if not with miraculous, yet with

great height or degree of divine faith, 'Yet Lord Thou canst save! Yet Lord

Thou canst save!' with such other expressions as I will forbear.

"upon which the ship did not only recover, but shortly after the violence of

the storm began to abate, and the Lord filled their afflicted minds with such

comforts as everyone cannot understand, and in the end brought them to their

desired haven, where the people came flocking, admiring their deliverance;

the storm having been so long and sore, in which much hurt had been done, as

the master's friends related to him in their congradulations."

MEANTIME, WHAT HAPPENED TO

THE WOMEN and children arrested at the creek?

"They were," said Bradford, "hurried from one place to another and from one

justice [of the peace] to another, till in the end they (the authorities) knew

not what to do with them; for to imprison so many women and innocent children

for no other cause but that they must go with their husbands, seemed to be

unreasonable and all would cry out of them.

"And to send them home again was as difficult; for they alleged, as the truth

was, they had no homes to go to, for they had either sold or otherwise disposed

of their houses and livings.

"After they had been thus turmoiled a good while and conveyed from one constable

to another, they (the authorities) were glad to be rid of them in the end upon

any terms, for all were wearied and tired with them. Though in the meantime

they, poor souls, endured misery enough; and thus in the end necessity forced

a way for them...

"And in the end, notwithstanding all these storms of opposition, they all gat

at length, some at one time and some at another, and some in one place and

some in another, and met together again according to their desires, with no

small rejoicing."

Bradford said there was a special "fruit" from the "troubles which

they endured and underwent in these their wanderings and travels

both at land and sea." For in

"eminent places"--Boston, Hull, Grimsby--"their cause became

famous"

because of their "godly carriage and Christian behavior" and they "greatly

animated others" to follow their example. There could have been

no greater delight to the Pilgrims, with their missionary zeal,

than that their example should attract others. [See,

persecution spread the Gospel, multiplied their numbers eventually.]

Entering wartime Holland seemed, said Bradford, "like they had come

into a new world--fortified cities strongly walled and guarded with

troops of armed men...a strange and uncouth language...different

manners and customs of the people with their strange fashions and

attires, all so far differing from that of their (the Pilgrims)

plain country villages..."

Their first views of Amsterdam, with the tower of its Oude Kerk

(Old Church) dominating the scene from the harbor, must have been

impressive indeed to these pastoral religious refugees. Formerly

a small fishing village on the Amstel River, just off the Zuider

Zee, Amsterdam had grown into a great metropolis during the Middle

Ages--a growth later magnified by an influx of merchants and artisans

from communities to the south, especially Antwerp, that had fallen

under Spain's control.

Amsterdam's ready access to the sea made it a natural homeport for

Dutch explorers and trading vessels, and for the shipment of its

manufactured goods. Navigators, among them the English explorer

Henry Hudson, sailed from this harbor with Dutch seamen to seek

both Northeast and Northwest passages to the Orient. Dutch ships

were already bringing riches from the Far East, and final plans

were nearly complete to establish a great world bank--something

then unknown in the British Isles.

AMSTERDAM, ABOVE ALL, WAS A

HAVEN from religious harassment. It also afforded the nearest and most

fruitful potential source of livelihood available to these displaced,

plundered, poverty-stricken farmers from England.

The last to flee from England across the North Sea with the women

and children had been their leaders, Rev. Robinson, Rev. Clyfton

and Brewster, who had "stayed to help the weakest over before them."

Now a new challenge arose in Amsterdam, a city described by Bradford

as "flowing with abundance of all sorts of wealth and riches...

"It was not long," he said, "before they saw the grim and grisly face of poverty

coming upon them like an armed man...

The newcomers, not being citizens, did not have access to membership

in the guilds that controlled the best-paid employment. Nor did

they have the required skills. For most, then, the only jobs available

were the poorest-paying--positions suited to beginners and the unskilled.

But "armed with faith and patience," the Pilgrims were dependable,

hard-working, uncomplaining.

Their presence in Amsterdam is associated chiefly with a narrow

alley called the Street of the Brownists, in the area between the

Old Church and the New Market--an area not far from the harbor where

they landed and in the oldest part of the city. It was here that

the Pilgrims joined in communion with earlier English immigrants

in the Ancient Church of Southwark, originally formed in London

by Rev. Johnson, who after a long imprisonment had escaped from

England and was again the congregation's pastor.

Indeed, Holland had welcomed thousands of refugees since the time

that the embattled William the Silent, a few years before his assassination,

declared to the magistrates of Middelburg: "You have no right to

interfere with the conscience of anyone so long as he works no public

scandal or injury to his neighbor."

[The Constitution of Rhode Island written by Roger Williams is a

direct reflection of this statement by William the Silent.]

The Pilgrims were eager to enjoy their religious freedom in peace,

but within a year they found that the harmony they sought was threatened.

For among the earlier English residents there arose dissension over

religious views.

Rev. John Smyth, who had fled from Gainsborough with his flock,

fell into contention with his former college tutor, Rev. Johnson.

These arguments were accompanied by flurries of contending religious

tracts and sermons. The climax came for the Pilgrims when, as Bradford

observed, "the flames of contention were like to break out in that

(Rev. Johnson's) ancient church itself, as afterwards lamentably

came to pass."

The Pilgrims, now intent on moving, selected the city of Leyden,

some 25 miles southwest of Amsterdam, as the haven where they would

live for more than 11 years.

REV. JOHN ROBINSON--INCREASINGLY ADMIRED for his peaceable nature,

common sense, learning, and wise, amiable guidance--became leader

of the Scrooby congregation. Their original pastor, Rev. Clyfton,

white-haired and much aged by his sufferings, had decided to remain

with Rev. Johnson at the Ancient Church. Bradford who got his first

religious teaching from Rev. Clyfton, said that the "reverend old

man...was loath to remove any more."

Though the second largest community in Holland, Leyden was less

than half the size of Amsterdam and did not have that city's easy

access to the sea. Yet the Pilgrims resolved to go there, "though

they well knew it would be much to the prejudice of their outward

estates...as indeed it proved to be."

Earning livelihoods would be much harder--a stern, unsuspected preparation

for the harsh life that would one day confront them in the wilderness

of faraway New England.

Above: Cells Guild Hall Boston England