|

Chapter V

In search of peace and spiritual comfort

The self-exiles find friendship, homes and jobs

in charming Leyden; however, a vengeful

King James continues to harass them.

Still in the Archives

in Leyden is a record of the official action taken on the

undated memorial, written in Dutch, that Rev. John Robinson

sent to the Leyden magistrates and that stated respectfully:

"Some members of the Christian Reformed religion, born in

the kingdom of Great Britain, to the number of 100 persons

or thereabouts, men and women, represent that they are desirous

of coming to live in this city by the 1st of May next; and

to have the freedom thereof in carrying on their trades, without

being a burden in the least to any one."

On Feb. 12, 1609, over the signature of one of their most

respected leaders, Jan van Hout, the Leyden magistrates hospitably

declared by way of response:

"They refuse no honest persons free ingress to come and have

their residence in this city, provided that such persons behave

themselves, and submit to the laws and ordinances; and therefore

the coming of the memorialists will be agreeable and welcome."

Not so to King James.

The Pilgrims had hardly bundled up their belongings and come

the canal route to Leyden--a passage westward toward Haarlem

and then southwest to Leyden--when the king's ambassador at

The Hague, only eight miles southwest of Leyden, informed

the Leyden magistrates of King James' displeasure.

In straight-faced, diplomatic manner, the magistrates sent

the ambassador copies of the correspondence with Rev. Robinson,

and claimed that they had acted "without having known, or

as yet knowing, that the petitioners had been banished from

England, or belonged to the sect of the Brownists...and request

that we may be excused by...His Majesty."

This reaction was in the well-known liberal spirit of van

Hout. The Leyden magistrates, of course--long accustomed to

furnishing haven to religious refugees and supporting the

reformist activity of their already famous university--well

understood the plight of the Pilgrims. Also, a 12-year truce

the Dutch signed with Spain in the spring of 1609 made the

subservience to the wishes of His Britannic Majesty less imperative.

King James, however, would be playing a strongly punitive

role against the Pilgrims during their stay in Leyden.

"Leyden...a fair and beautiful city and of a sweet situation,

but made more famous by the university wherewith it is adorned,

in which of late had been so many learned men." In those words

Bradford pinpointed the community's chief attractions, particularly

the renown of its professors. One of them, Johannes Polyander--who

would play an important part in the Pilgrims' dealings with

King James--in telling friends of his house beside one of

Leyden's numerous, Venice-like canals lined with linden trees,

concluded: "I am lodged in the most beautiful spot in the

world."

Leyden, like much of Holland, has the appearance of a low-lying

meadow save for an artificially raised hill at the point where

two branches of the Old Rhine, flowing in from the east, join

near the city center and flow as a broader stream westward

out of the city. On the hill, called the Burgh, was in early

times a fort and later a castle.

Quick employment was a critical need for the Pilgrim newcomers.

Leyden had long been a center of the fine-cloth trade. A lot

of the wool goods exported from England, enriching ports like

Boston [England], were manufactured into cloth in Leyden.

In those days, however, this did not mean that there were

immense mills. Manufacturing mostly meant work on handlooms

in individual houses, with the clothing entrepreneur furnishing

the working materials, and warehousing and trading the finished

products.

Most of the Pilgrims got jobs in the cloth industry, the greatest

number of weavers in wool, silk, linen, fustian or bombazine

(a form of silk with a special weave). Some were wool combers

and wool carders. Some made gloves, ribbon and twine. A few

were merchants. Some tried several jobs, from baker to printer.

"They fell to such trades and employments as they best could,"

said Bradford, "and at length they came to raise competent

and comfortable living, but with hard and continual labor."

At first their lodgings were in the newer part of Leyden,

a city which, like Amsterdam, was expanding as it prospered.

Costs were lowest there, in the northwest area of the community,

and so there the Pilgrims "pitched" (settled). Above all,

they valued peace, said Bradford, and "their spiritual comfort

above any other riches whatsoever.

"They continued many years in a comfortable condition, enjoying

much sweet and delightful society and spiritual comfort together

in the ways of God, under the able ministry and prudent government

of Mr. John Robinson and Mr. William Brewster who was an assistant

unto him in place of an Elder, unto which he was now called

and chosen by the church.

"Such was the true piety, the humble zeal and fervent

love of this people, whilst they thus lived together, towards

God and His ways, and the singleheartedness and sincere affection

one towards another, that they came as near the primitive

pattern of the first churches as any other church of these

later times have done...."

On May 5, 1611, Rev. Robinson and some members of the church,

including his brother-in-law, completed the purchase of a

house "formerly called Groene Port (Green Gate)," which had

a garden and a big vacant parcel of land in the rear. The

purchase was on behalf of the entire church, the price 8000

guilders (equal then to 1400 pounds [British pound of 1850

was equal to $5] ), with one-fourth down and an annual mortgage

payment of 500 guilders--a big debt.

Green Gate, which was used as a parsonage for Rev. Robinson

and his family, is the place most associated with the Pilgrim

stay in Leyden, though long since demolished. It was here

that the Pilgrim congregation met and held its divine services.

The house was located in the old center of Leyden on the south

side of the hof (square) surrounding the foremost landmark

in the city, St. Peter's Church, a former cathedral built

in the early thirteenth century.

The house faced Bell Alley [a 1660's Sabbatarian Christian

congregation was located in Bell Lane, London and was called

the Bell Lane Church of God, from which Steven Mumford and

his wife came from before they settled in Providence, Rhode

Island.] The entrance to the old cathedral was just across

the alley. A visitor leaving the house and turning left would

very quickly arrive at the linden-bordered canal outside Professor

Polyander's house, and by then crossing the bridge over the

canal, would arrive directly at the University of Leyden.

A right turn on leaving Green Gate, and a walk of similar

distance and another landmark, the Stadhuis (City Hall), an

ornate medieval structure.

The house, under lease when purchased, was not available for

another year. But the big parcel of land was accessible and

a carpenter member of the congregation, William Jepson, began

construction of 21 shall dwellings for members of the church.

Rev. Robinson moved into Green Gate on May 1, 1612. None of

the Pilgrims has left a description, but we can readily imagine

their thanksgiving service or their springtime gathering in

Green Gate's garden, with its well that was the watering place

for all those small dwellings built by Jepson. Bradford has

left a happy picture of Robinson and his flock:

"His love was great towards them; and his care was always

lent for their best good, both for soul and body. For besides

his singular abilities in divine things, wherein he excelled;

he was also very able to give directions in civil affairs,

and to forsee dangers and inconveniences: by which means he

was very helpful to their outward estates; and so was, every

way, as a common father unto them."

The many extant records at City Hall--public records of marriages,

citizenship, real estate, mortgages--furnish vivid glimpses

of Pilgrim life in Leyden.

Bradford became a citizen of Leyden in the year Rev. Robinson

took over Green Gate. Bradford, now of age, had come into

an inheritance from his family estate back in Austerfield.

He arranged to acquire a house of his own and the following

year walked with his witnesses up the magnificent staircase

of City Hall for his marriage to Dorothy May, 16-year-old

daughter of the elder of the Ancient Church in Amsterdam.

The groom was 23.

Bradford told how "many came unto them (the Pilgrims) from

divers parts of England; so as they grew to a great congregation."

In all, the congregation grew during the Pilgrims' time in

Leyden to some 300 parishioners. Word of the Pilgrims had

gone far beyond the "eminent places" near Scrooby--Boston,

Hull and Grimsby. Newcomers came from Amsterdam's Ancient

Church, from London, and from shires from Yorkshire to Kent. [Their persecution and steadfastness in endurance won many souls, which swelled their ranks.]

The new members included some of the most prominent of the

Pilgrims. There was Isaac Allerton, a London tailor, who would

become a merchant and magistrate in the New World. There were

three who would become deacons in Leyden: Robert Cushman,

a wool comber from Cantebury; Samuel Fuller, a maker of silk,

satin and serge from London; and John Carver, a Yorkshire

merchant and brother-in-law of Rev. Robinson. And there was

Edward Winslow, a London printer and a future colonial governor.

The names of all of these, save Carver, are among those on

the marriage rolls, which record nearly 50 Pilgrim weddings

in Leyden. Carver, who would be the first governor of the

Pilgrims in the New World, had married the older sister of

Rev. Robinson's wife before coming to Holland.

THERE WERE NEARLY

100 CHILDREN IN THE PILGRIM church during the time in Leyden--a

pleasant, family picture. They were contemporaries of the

artist Rembrandt, a child in Leyden in those years.

But there was a sad side, too. Childbirth was often fatal

in those times, and burial records tell mournful tales. The

saddest is of a friend of Brewster, Thomas Brewer, who within

two months lost a child, and then his wife and another son

in childbirth.

The Pilgrims' simple, steadfast, industrious way of

life brought "good acception" from their neighbors.

"Though many of them were poor," said Bradford, "yet there

was none so poor but that if they were known to be of that

congregation (Brownists), the Dutch, either bakers or others,

would trust them in any reasonable matter, when they wanted

money; because they had found by experience, how careful they

were to keep their word; and saw them so painful (painstaking)

and diligent in their callings. Yes, they would strive to

get their custom (business); and to employ them above others

in their work, for their honesty and diligence."

In back of the land where the Pilgrims built 21 small houses

was the former Veiled Nuns' Cloister. The Leyden magistrates

assigned the lower floor as the gathering place of the Reformed

Scotch Church. The broad-minded pastor of the Pilgrims, Rev.

Robinson, was friendly with the minister and members of this

church, and they would at times hold communion together.

The clergyman's scholarship, like his tolerance, attracted

many admirers, especially in the university. Soon after his

arrival in Leyden Rev. Robinson, like many other exiled clergy

on coming to Holland, published his opinions. He wrote a book

A Justification of Separation, that was a theological

defense of noncompliance with England's state church. He frequented

the library of the university, conveniently located in the

upper floor of the nearby Cloister.

In the fall of 1615 Rev. Robinson was admitted to the university

as a student of theology. Many advantages accompanied this

honor: Tax exemption, exemption from the service in the city

guard, and allowances of 10 gallons of wine every three months

and 126 gallons (half tun) of beer every month--very welcome

in an era without tea, coffee, soft drinks or a generally

safe water supply.

"Great troubles" that "greatly molested the whole state" arose

at this time, Bradford said, over what was called the Arminian

controversy--a hot religious dispute that attracted the heavy

hand of King James.

Jacobus Arminius, who up to his death was a professor of theology

at the university, had preached that individuals by their

own action can win salvation. This went against the rigid

teaching of the Calvinists that man's salavation was a matter

of heavenly predestination. The university had professors

on both sides of the controversy and Rev. Robinson attended

their rival lectures despite his heavy schedule of writing

"sundry books" and giving three lectures a week to his congregation.

King James went so far as to persuade the Dutch authorities

to influence the university to reject the candidate chosen

to succeed Prof. Arminius.

Rev. Robinson was brought into the controversy by his friend

Prof. Polyander, orthodox advocate of the Calvinist doctrine.

The clergyman, said Bradford, "was loath, being a stranger."

But the professor anxiously importuned Rev. Robinson with

the appeal that "such was the ability and nimbleness of the

adversary that the truth would suffer if he (Rev. Robinson)

did not help..."

The Pilgrim pastor ultimately delivered three university lectures

and won "much honor and respect." But the grateful university

refrained from heaping any "public favor" on Rev. Robinson

to avoid "giving offense to the state of England"--namely

King James.

In later developments in the controversy--developments that

gravely endangered the unity of Holland--King James got the

Dutch government to further twist the university's arm and

prevent the famous English divine, Rev. William Ames, from

joining the university's faculty.

Rev. Ames was a friend or tutor to all the clergy who would

fill the first pulpits in New England. Only his death prevented

him from coming to the New World in later years. But his teaching--his

use of direct, forceful language--shaped the sermons preached

to early New Englanders. And his book for long was the principal

theological text at the first training ground for New England

clergy, Harvard College.

Harsher tactics than those used against Rev. Ames

were employed by King James against William Brewster and his

underground press.

Brewster, who had suffered the "greatest loss" in the flight

from Scrooby to Holland, had financial difficulties that were

the more burdensome because of his age. In those early years

"he suffered much hardship," said Bradford. "[as] he had spent

the most of his means, having a great charge (expense) and

many children; and, in regard of his former breeding and course

of life, not so fit for many employments as others were; especially

such as were toilsome and laborious. But yet he ever bore

his condition with much cheerfulness and contentation (contentment)."

Brewter's schooling at Cambridge came to his aid. He could

speak Latin, the scholar's language. The University of Leyden

drew many students from Denmark and Germany. Brewster prepared

a book of rules, in the style of Latin grammar books, and

taught English in his dwelling. "Many gentlemen, both Danes

and Germans," said Bradford, "resorted to him, as they had

time from other studies; some of them being great men's sons."

BREWSTER'S GREATEST SOURCE OF HELP HOWEVER,

was Thomas Brewer, a wealthy gentleman from Kent who came

to live in Leyden, in a house he purchased in Bell Alley just

a door but one from Rev. Robinson's Green Gate. It was called

Green House.

Brewer, a man in his late 30s, about 10 years younger than

Brewster, was a member of the Reformed Scotch Church. He was

a Puritan zealous to spread the gospel. He made his house

a center for students, among them a doctor and a future minister

of his church. Brewer himself was enrolled in the University

of Leyden as a scholar in literature.

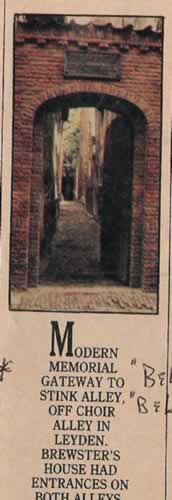

Chiefly with Brewer's financing, Brewster was able

late in 1616 to make arrangements for publishing from his

dwelling on Stink Alley, a narrow passageway off Choir Alley,

which runs from the main city street with its City Hall to

the square surrounding St. Peter's Church, entering the square

toward the rear of the church. Brewster's L-shaped, three-family

house also had an entrance on Choir Alley.

Brewster and his helpers had "employment enough,"

said Bradford; "and by reason of many books which would not

be allowed to be printed in England, they might have had more

than they could do."

Financial aid made it possible for Brewster, who was not a

printer himself, to secure a master printer from London, John

Reynolds. With Reynolds came an apprentice printer,

or assistant, who would become a most prominent Pilgrim. He

was Edward Winslow, then 21 years of age. They both

lived in Brewster's house, and, when they soon went with their

brides to be married at City Hall, members of the Brewster

family went as attendants.

Brewster's publications were far more religious than

commercial in nature. The first few books, in Latin and Dutch,

bore his name; the date, 1617; and the words In Vice Chorali,

which is the Latin translation of Choir Alley and the name

most often associated with Pilgrim activities. The fact that

none of the first three books was in English and that only

those bear the Brewster imprint indicates that they were intended

to provide later printing with protection.

Eventually some dozen-and-a-half books came from Choir Alley,

which would keep such a small enterprise very busy. Later

events, when the authorities raided the premises, suggest

that no press work was done there and that the type, when

set, was taken for printing to Dutch shops.

Significantly, Prof. Polyander wrote a preface to Brewster's

first book, a Latin commentary on religious proverbs. Brewster's

printing had other associations with the university, including

tracts on the Arminian controversy. One of his other

earliest books was a polemic by Rev. Ames, who was such a

personal source of irritation to King James even though the

clergyman was one of those Puritans who wanted to stay within

the state church.

Late in 1618, with Europe about to be plunged into the devastation

and agony of the Thirty Years War, and with Prince Maurice

of Orange eager for English assistance, King James was able

to get the Dutch ruler to issue an edict that prohibited

foreigners in Holland from printing books objectionable to

friendly foreign countries.

King James had reason. Earlier that year, in August,

he had called a church synod at Perth, the ancient capital

of Scotland, in an effort to impose a hierarchical structure

of bishops over the presbyters, the elders, of the Scottish

church.

The Scots were unalterably opposed. The historian of the Scottish

church, nonconforming David Calderwood, wrote a tract denouncing

the Perth Assembly. To get it printed, he fled to Holland,

and in a few months Perth Assembly, printed with type from

Brewster's fonts, appeared in Scotland. It had been smuggled

into Scotland concealed in wine vats. King James was incensed.

[PERTH ASSEMBLY denounced efforts by King James to impose

a hierarchy of bishops on the Scottish church.]

The captain of the guard in Edinburgh, on the king's orders,

searched the "booths and houses" of three booksellers there

but found neither Perth Assembly nor the author.

An innocent Scottish bookseller who happened to be in London

was seized and brought before the angry king. "The devil take

you away, both body and soul," raged King James to the kneeling

bookseller, "for you are none of my religion." As for his

Scottish subjects in general, the king added: "The devil rive

(split) their souls and bodies all in collops (slices), and

cast them into hell!" The bookseller was unjustly kept in

prison for three months.

In July 1619 His Majesty's ambassador at The Hague, Sir Dudley

Carleton, came across some copies of Perth Assembly

and some clues. He hurried off a message to King James' secretary

of state, Sir Robert Naunton, at Whitehall Palace: "I am informed

it is printed by a certain English Brownist of Leyden, as

are most of the Puritan books sent over, of late days, into

England." In view of the new Dutch edict, Carleton said that

he would complain to the Dutch authorities.

Five days later Carleton hustled off another note

to Naunton in which he said that the culprit was "one William

Brewster, a Brownist, who hath been, for some years, an inhabitant

and printer at Leyden; but is now within these three weeks...gone

back to dwell in London...where he may be found out and examined."

If Brewster was not the printer, advised Carleton, "he assuredly

knows both the printer and the author."

Carleton was right. Brewster was already in England and some

three months earlier--doubtless aware of the royal manhunt--had,

as Pilgrim Deacon Robert Cushman, then in England, wrote the

Pilgrims back in Leyden, gone "into the north" of England.

Brewster, sought by the authorities in three countries--England,

Scotland and Holland--had gone underground.

Now began something of a comedy of errors. The sleuths were

unquestionably misled by friends of Brewster, particularly

his friends at the University of Leyden, where his tutoring

of scholars had made him quite popular.

Naunton wrote Carleton that Brewster was not to be found in

London and that he must be somewhere in Holland. Carleton

wrote back that he was informed Brewster was not only not

in Leyden but unlikely to be there any time soon, "having

removed from thence both his family and goods..."

From King James came something more menacing for the Dutch,

eager for his good will. The king had commanded him, Naunton

said, to tell Carleton to "deal roundly with the State-General

(the Dutch central government) in his name, for the apprehension

of him, the said Brewster, as they tender (value) His Majesty's

friendship."

Carleton began to get hints that Brewster was in Leyden...no

maybe Amsterdam. He had searches made, keeping Naunton (and,

of course, the irritated king) informed.

Then, suddenly, Carleton triumphantly informed them that Brewster

had been taken in Leyden. But Carleton was quickly forced

to get off another message explaining that he was in error--an

error caused by a bailiff, "a dull, drunken fellow (who) took

one man for another."

The man under arrest was Brewster's benefactor, Thomas Brewer.

Brewer told the authorities that "his business heretofore

had been printing, or having printing done," but he blandly

explained that he had quit any printing the prior December

because of the edict making it illegal. He identified Brewster

as "his brother," but, by way of throwing the pursuers off

scent, said that Brewster was "in town at present, but sick."

The bailiff, now certainly sober, rechecked and reported that

Brewster "had already left" Leyden. Brewer, being "a member

of the university," was now transferred to the university

authorities. When the bailiff asked assistance from the university

in seizing the illegal printing supplies, university officials--most

likely with tongue in cheek--appointed Prof. Polyander, Brewster's

friend, to help him.

THEY FOUND "THE TYPES"

IN THE GARRET OF Brewster's former dwelling in Stink Alley.

They made a catalogue of the books found. Then the bailiff

had "the garret door nailed in two places, and the seal of

the said officer, impressed in green wax over the paper, is

placed upon the lock and the nails..."

Naunton wrote consolingly to Carleton:

"I am sorry that Brewster's person hath so escaped you;

but I hope Brewer will help you find him out."

Brewer did no such thing.

It was now, however, that Rev. Ames' desire for appointment

at the University of Leyden was wrecked. In going over the

catalogue of Brewster's books, Carleton noticed that Rev.

Ames "hath his hand in many of these." Carleton told Naunton

he therefore "desired the curators of the University of Leyden

not to admit him (Rev. Ames) to a place of public professor...until

he hath given His Majesty full satisfaction." That, given

the king's attitude, was impossible.

The king's request ran headlong into difficulties raised by

the university. Its officials were unwilling to remand Brewer,

and felt they should be the ones to try him. Carleton got

the Prince of Orange to speak personally with the university

rector. Finally Prof. Polyander arranged a compromise: Brewer

was to go "voluntarily" to England, with the assurance that

he could return to Holland within three months free of expenses,

and unharmed.

Carleton called Brewer "a professed Brownist" who had "mortgaged

and consumed a great part of his estate...through the reveries

(dreams) of his religion." Questioning of Brewer in London

proved futile. Naunton wrote Carleton that Brewer "did all

that a silly creature could to increase his (the king's) unsatisfaction."

Brewer was discharged. But he did not return to Holland.

A few years later Brewer, persecuted by the bishops for aiding

gatherings of nonconformists in Kent, was fined 1000 pounds

and imprisoned. He remained in King's Bench Prison for 14

years, until he was released by act of the Long Parliament,

on the eve of the civil war against King James' son and successor,

Charles I.

Brewster, in heading "into the north," may well have

avoided a much worse fate than Brewer's, with King James--called

"the wisest fool in Christendom" by the chief minister of

a French monarch--thirsting for his arrest.

|