| Chapter VII

Setting sail towards a little-known land

The Mayflower starts across the ocean, but 'to most

of these essentially plain farm folk, their real transport

was more their faith in God than their vessel.'

Prayer--an appeal for

God's guidance--came first into the minds of the Pilgrims

upon receipt of the news that their migration to the New World

was finally to get under way.

"They had a solemn meeting and a day of humiliation [fasting],

to seek the Lord for his direction," said Bradford. Their

pastor, Rev. Robinson, preached a sermon recounting the biblical

story of how "David asked counsel of the Lord." The clergyman

then spoke comforting words, "strengthening them against their

fears and perplexities; and encouraging them in their resolutions."

Even if the Pilgrims were all ready to go together, however,

they lacked the "means to have transported them." They decided

that if a majority were to have their affairs in order, and

thus be able to leave, Rev. Robinson would accompany them

as their pastor; if not, they desired that Brewster should

go as their elder.

Those going would "be an absolute church of themselves, as

well as those that stayed: seeing, in such a dangerous voyage

and a removal to such a distance, it might come to pass they

should, for the body of them, never meet again in this world."

Still, all would continue as members of the faith, whether

in Holland or the New World, "without any further dismission

(dismissal) or testimonial."

Winslow told of two other major decisions made by the congregation

at this time: "They that went should freely offer themselves"

and "the youngest and strongest part" should go first.

Another day of solemn humiliation was held when notice came

from Delftshaven--a port near Rotterdam on the River Maas

that was a little more than 20 miles to the southwest by canal--that

the Speedwell with its new masts and sails, was ready.

Rev. Robinson, the beloved pastor, preached his final sermon

for the departing Pilgrims. He read a lesson from the Bible

that to seek God was "a right way for us and for our children.

He spent a good part of the day very profitable and suitable

to their present condition," said Bradford, and there were

fervent prayers "mixed with abundance of tears."

Winslow later recalled some of the clergyman's words: "Whether

the Lord had appointed it or not, he charged us before God

and His blessed angels, to follow him no further than he followed

Christ."

The broad-minded pastor exhorted them that "if God should

reveal anything to us by any other instrument of His, to be

as ready to receive it as ever we were to receive any truth

of his (Rev. Robinson's) ministry; for he was very confident

the Lord had more truth and light yet to break forth out of

His holy word.

"Another thing he commended to us, was that we should use

all means to avoid and shake off the name of Brownist, being

a mere nickname and brand to make religion odious...and to

that end, said he, I should be glad if some godly minister

would go over with you before my coming."

The clergyman, who would be frustrated from ever going to

the New World, told them, "Be not loath to take another pastor

or teacher...for that flock that hath two shepherds is not

endangered but secured by it." The Pilgrims would hope for

years that Rev. Robinson would rejoin them, but in vain. Meanwhile,

his robe as teacher would be filled by Elder Brewster.

Next day most of this close-knit fellowship made the canal

passage together, moving through Delft, the Dutch capital

and burial place of the martyred champion of religious freedom,

William the Silent, and on to Delftshaven.

In a final remark on their departure from Leyden, Bradford

gave them the name by which they would generations later become

known to history:

"They know they were Pilgrims," he said, "and they

looked not much back on the pleasant city that had sheltered

them, but lift up their eyes to the heavens, their dearest

country, and quieted their spirits." Their final

hours with their friends--for most would never again see one

another on earth--were poignantly described by Bradford:

"When they came to the place (Delftshaven), they found the

ship and all things ready; and such of their friends as could

not come (to the New World) with them, followed after them;

and sundry also came from Amsterdam to see them shipped, and

to take their leave of them.

"That night was spent with little sleep by the most; but with

friendly entertainment, and Christian discourse, and other

real expressions of true Christian love.

"The next day, the wind being fair, they went aboard and their

friends with them; when truly doleful was the sight of that

sad and mournful parting. To see what sighs and sobs and prayers

did sound amongst them; what tears did gush from every eye,

and pithy speeches pierced each heart: that sundry of the

Dutch strangers that stood on the quay as spectator, could

not refrain from tears.

"But the tide, which stays for no man, calling them away that

were thus loath to depart: there reverend Pastor, falling

down on his knees, and they all with him, with watery cheeks,

commended them, with most fervent prayer, to the Lord and

his blessing. And then, with mutual embraces and many tears,

they took their leaves one of another; which proved to be

the last leave to many of them."

A martial touch--for all ships, in fear of pirates, traveled

armed in those days--was recalled by Winslow:

"We gave them a volley of small shot (musket fire) and of

three pieces of ordnance. And so lifting up our hands to each

other; and our hearts for each other to the Lord our God,

we departed--and found His presence with us, in the midst

of our manifold straits that He carried us through."

It was Saturday, July 22, 1620. The Speedwell went past the

Hook of Holland" at the mouth of the Maas, and across the

North Sea to the English Channel. They had a "prosperous wind"

and in a short time the small ship entered the great harbor

of Southampton, where the Pilgrims found the Mayflower from

London already berthed, and the Strangers who would make up

the rest of their company.

There was "a joyful welcome and mutual congratulations," said

Bradord, "with other friendly entertainments..."

There were familiar faces: Carver and Cushman, so long away

on months of negotiation and preparation; and most of all

there was their elder, Brewster--though he was constrained

to some disguise until distance should give him a feeling

of security from sudden arrest.

This was the first meeting of the Pilgrims and the Strangers--men,

women and children recruited mostly in and about London, East

Anglia and the southeastern section of England.

For most of the Strangers, though they would become known

as Pilgrim forefathers, the attractions offered by the adventurers

were chiefly economic--a chance to own land, and to escape

the poverty being spread in England by inflation and by farmers

being forced from their land for the more profitable raising

of sheep.

If all the hired hands and servants were excluded, the Strangers

would come close to outnumbering the Pilgrims.

One of the Strangers was Capt. Myles Standish--in his mid

30s, a short man with a florid countenance, a man who had

served with the English volunteers fighting in Holland to

aid the Dutch, and who would become the Pilgrims' celebrated

military right arm in the New World. Two other Strangers would

become assistant governors: Stephen Hopkins, who had already

made one trip to the New World and had been shipwrecked in

Bermuda; and Richard Warren, a London merchant.

The Strangers brought problems, too--in the form of the profane

John Billington of London, whom the Pilgrims would have to

hang a decade later for murder; and of two of Hopkins young

servants, who would fight a duel.

There were five hired hands: a cooper and four sailors. The

cooper, a 21-year-old blond man from East Anglia, was John

Alden. Alden would settle in the New World and marry the daughter

of a Stranger, Priscilla Mullins, who would utter the legendary

words to her hesitant lover, "Why don't you speak for yourself,

John?"

The lean purse of the Pilgrims and the tightfisted behavior

of the adventurers underscored money problems at Southampton.

These were compounded by differences that arose among the

three men who had obtained the provisions--at three different

places, a fact that had evoked the disapproval of Thomas Weston.

Especially disturbing to Cushman, who played the impossible

role of diplomat, was the attitude of Christopher Martin,

named a purchasing agent to represent the Strangers, had been

chosen treasurer by the adventurers.

A stubborn man, Martin purchased freely, without consulting

the Pilgrim agents, and drove the Pilgrims' financing into

a muddle that years of effort would fail to clarify or correct.

Cushman said that nearly 700 pounds had been spent at Southampton,

"upon what I know not." Martin, Cushman protested, "saith,

he neither can, nor will, give any account of it. And if he

is called upon for accounts, he crieth out of unthankfulness

for his pains and care, that we are suspicious of him: and

flings away...Who will go and lay out money so rashly and

lavishly as he did, and never know how he comes by it?"

Ominously the Speedwell, which had shown some sailing quirks

on the passage from Holland, cut into the Pilgrims' skimpy

funds. It had to be "twice trimmed at Southampton."

The worst moments at Southampton, though, came with the arrival

of Thomas Weston, and with his efforts to get the emigrants

to agree to the altered terms demanded by some of the adventurers

in the seven-year contract. On this, the irascible Martin

felt like the people from Leyden: The adventureres, Martin

told Cushman, "were bloodsuckers!" (Martin must have meant

this for all the others, for he had ventured 50 pounds himself.)

CAPT. JOHN SMITH,

IN HIS GENERALL HISTORIE wrote that the adventurers were about

70 in number--"some gentlemen, some merchants, some handycrafts

men, some adventuring great sums, some small, as their estates

and affection served." They were a voluntary combination,

not a corporation, and "dwelt mostly about London."

The adventurers well knew, Smith said, that establishing a

plantation could not be done "without charge, loss and crosses."

Many would "adventure no more," because the general stock

had already cost 7000 pounds.

Weston, clearly not an entirely free agent, was "much offended

when the Pilgrims told him that he knew right well the original

terms, and that their agents had been enjoined when they left

Leyden not to agree to any new terms "without the consent

of the rest that were behind." And when they told him that

the enterprise needed "well near 100 pounds" to clear Southampton,

Weston told them that he would not dispense another penny.

He promptly headed back to London, telling the Pilgrims angrily

that they could now "stand on their own legs."

After a discussion, the conscientious Pilgrims wrote a letter

to the merchants and adventurers making a new offer.

They expressed their sorrow that "any difference at all be

conceived between us." They said that the possibility of owning

their own houses and lands "was one special motive, amongst

many others, to provoke us to go," and that they had never

given Cushman assent to make the change designating such property

part of the company's stock. Still, they offered, "that if

large profits should not arise within the seven years, that

we will continue together longer with you, if the Lord give

a blessing."

They understood, they said, that three-fourths of the adventurers

were not insisting on the harsher terms; and as for their

own plight:

"We are in such strait at present as we are forced to sell

away 60 pounds worth of our provisions, to clear the haven

(the port); and withal put ourselves upon great extremities;

scarce having any butter, no oil, not a sole to mend a shoe,

nor every man a sword to his side; wanting (lacking) many

muskets, much armor, etc. And yet we are willing to expose

ourselves to such eminent dangers as are like to ensue, and

trust to the good Providence of God..."

Capt. Smith, a tireless promoter of plantations in New England,

later put in perspective what the Pilgrims were about to do.

Since his explorations of New England in 1614, Smith wrote,

the region's fame had grown so "that 30, 40 or 50 sail went

yearly only to trade and fish.

"But nothing would be done for a plantation till about some

100 of your Brownists of England, Amsterdam and Leyden, went

to New Plymouth: whose humorous ignorances caused them, for

more than a year, to endure a wonderful deal of misery with

an infinite patience; saying my book and maps were much better

cheap to teach them than myself."

Smith had offered his services to the Pilgrims and had been

turned down. After all, they did not think they were headed

for New England; and Weston and Cushman had already hired

pilots who had been to America. Anyway, they did indeed have

Smith's book and maps.

Departure this time included no farewells from friends.

A governor, with two or three assistants, was chosen for both

of the vessels "to order the people...and to see to the disposing

of provisions and such like affairs." All this was agreeable

to the skippers of the ships. Martin was chosen for the Mayflower,

Cushman for the Speedwell.

About the only ceremony was a calling together of all the

company to hear a letter that had arrived from Rev. Robinson.

He wished he could be with them. He had final words of advice,

especially that, since they were about to govern their own

affairs, they choose people who "do entirely love and will

promote the common good...yielding unto them all due honor

and obedience in their lawful administrations..."

The two vessels sailed Aug. 5--belatedly, but not

yet disastrously late if all would soon go well. [1st try]

But they had not gone far before Master Reynolds found the

Speedwell so leaky that "he durst not put further

to sea till she was mended." He signaled Christopher Jones

of the Mayflower, and came aboard the larger vessel

to confer, and they decided to put into the port of Dartmouth

for repairs. Reynolds had abundant grounds for concern.

Cushman, feeling ill, was deeply disturbed about trying to

justify his actions accepting the oppressive seven-year contract,

and further upset by Martin's high-handed treatment of the

Pilgrims and sailors aboard the Mayflower. He wrote

of his troubles to a friend in London, and also told about

the Speedwell's shocking condition:

"She is as open and leaky as a sieve; and there was a board

two feet long, a man might have pulled off with his fingers,

where the water came in as at a mole hole...If we had stayed

at sea but three or four hours more she would have sunk right

down."

Earlier, the need to trim Speedwell twice at Southampton

had consumed an extra week of fair weather. "Now we lie here

waiting for her in as fair a wind as can blow...Our victuals

will be half eaten up, I think, before we go from the coast

of England, and if our voyage last long, we shall not have

a mouth's victuals when we come in the country."

Bradford said that the Speedwell was "thoroughly

searched from stem to stern, some leaks were found and mended,

and now it was conceived by the workmen and all, that she

was sufficient, and they might proceed without either fear

or danger." They set out again on Aug. 23 "with good

hopes." [2nd try.]

But all was not well. By the time they were more than 100

leagues (roughly 300 miles) at sea--well into the Atlantic

and far beyond Land's End--Master Reynolds again signaled

for a conference. Frantic pumping could "barely keep up with

the leaks" in the Speedwell. Reynolds said he must

"bear up or sink at sea." So they turned back and put into

the nearest big port. Plymouth Harbor, where they were certain

to obtain expert help.

This harbor, in the western part of England and the English

Channel, had long been famous in England's wars, seafaring

and worldwide exploration. The governor of both the fort and

port was a man of ancient English lineage, Sir Fernando Gorges,

one of the foremost champions of plantations in the New World.

Gorges, now in his mid-50s, was a soldier--knighted by the

earl of Essex on the battlefield--and a courtier with considerable

influence with King James. At the very moment the Pilgrims

arrived in the port, Gorges had pending before the Privy Council

his request for a new charter to convert the old Virginia

Company of Plymouth into the Council for New England.

No one would be happier than Gorges at the sight of these

two vessels entering his harbor--vessels intending to voyage

to the New World to begin a plantation. This was something

Gorges had been trying to achieve since the beginning of the

century, when a returning explorer, George Wymouth, presented

him with some Indians--an event that aroused Gorges' hopes

of using the Indians as interpreters and guides in founding

colonies.

Gorges, who would become know as the "Father of Maine" though

he would not personally ever set foot in America, had steadfastly

persisted in his efforts despite repeated and costly failures.

Right now, he was being forwarded reports from the explorer-trader-agent,

Capt. Thomas Dermer, whom he had sent to the Plymouth area

marked on Capt. Smith's map--the identical area where these

Pilgrims would by chance [where God is involved, rabbi's say

the word coincidence (or chance) is not a Kosher

word] establish New England's first permanent English plantation.

The Pilgrims were well-received by Gorges' people and by the

townspeople while Speedwell was examined once again.

The finding, though, was not good.

"No special leak could be found," said Bradford, "but it was

judged to be the general weakness of the ship, and that she

would not prove sufficient for the voyage. Upon which it was

resolved to dismiss her and part of the company, and proceed

with the other ship. The which, though it was grievous and

caused great discouragement, was put in execution."

Provisions and supplies had to be transferred from the Speedwell's

hold to the Mayflower. The worst wrench was that the number

of passengers had to be reduced by 20. Still, Bradford observed,

"those that went back were for the most part such as were

willing to do so, either out of some discontent or fear they

conceived of the ill success of the voyage..."

Among them was Cushman, still ill, and feeling the unmerited

harassment that he was bearing "like a bundle of lead...crushing

my heart." Bradford in his journals quoted Cushman, in a letter

to a friend in London, as seeing "the dangers of this voyage

[as]...no less deadly...If ever we make a plantation, God

works a miracle!" Such, said Bradford, were Cushman's fears

at Dartmouth; and, he added, "They must needs be much stronger

now..."

This was severe on Cushman. Bradford was equally severe on

Master Reynolds. Bradford agreed that overmasting--putting

excessively large masts into the reconditioned Speedwell--had

naturally opened its seams when the ship was under heavy sail.

But he suspected that Reynolds had done this deliberately

when supplies seemed to be falling low, so that he and the

crew, signed on for a year, could get out of their contract.

In after years, Bradford noted, once the Speedwell was refitted

she "made many voyages...to the great profit of her owner..."

Overall, the Speedwell venture had turned out ruinously

in loss of time; and this loss, protracting the Pilgrims'

passage into the raging autumnal storms of the Atlantic, would

contribute to exacting a dreadful toll in lives of the brave

men and women and children--and tragically as well in those

of the crew.

Already it was some 45 days since they had left Holland--sufficient

time to have completed a normal crossing of the Atlantic--and

the Pilgrims only now saw the sails raised and the vessel

about to depart from Plymouth Harbor.

It was Sept. 6. [3rd try, final departure.]

They had, said Bradford, "a prosperous wind which continued

divers days together" as their passage resumed. Many, though,

were shortly "afflicted with seasickness."

Soon they again passed Land's End and the Isles of Scilly.

They were beyond the English Channel. Ahead of them--the only

thing between them and the New World--was the Atlantic Ocean,

a vast, awesome expanse.

To most of those essentially plain farm folks, their real

transport was more their faith in God than their vessel.

And of this faraway land they hoped to reach, their future

home, what was known to these Pilgrims in the year 1620? What

had been discovered?

IN HIS DIARIES, BRADFORD TOLD OF EXPLORATIONS

in future New England, in particular mentioning explorers

Bartholomew Gosnold, who in 1602 christened Cape Cod--where

the Pilgrims would make their first New World landfall--and

Thomas Dermer, who visited the future Plymouth at Gorges'

behest "but four months" before the Pilgrims would arrive

there. [If this wasn't a Providential setup, I'll eat my hat!]

One explorer, 23-year-old Martin Pring, began voyaging to

America in 1603. He made landfall in present Maine, then came

down the coast to future Plymouth, which the Patuxet Indians

called Accomack. Unlike the Pilgrims, he found no dearth of

Indians. They came, he said in a later account, "sometimes

10, 20, 40 or threescore, and at one time 120 at once..."

By the time the next major English explorer, Capt. Smith,

came to the same harbor in 1614, England had its first colony

in North America, struggling and suffering Jamestown. Smith

had been part of that colony, serving as its governor and,

later, as its historian.

Now, however, he was on an expedition of two ships, financed

by four London merchants, with orders "to take whales and

make trials of a mine of gold and copper." They chased, but

could catch no whales. There were no mines, either, so they

turned to fish and furs. While thirty-seven of his crew fished

off Maine's Monhegan Island, Smith and eight or nine of his

sailors ranged the coast, trading for beaver, marten and otter

skins.

On his famous exploration of the coast from the Penobscot

River in Maine to the tip of Cape Cod, Smith found the Indians

were friendly in general: and even after a scrap at future

Plymouth, all again "became friends." In his search he found,

he said: "Not one Christian in all the land."

Smith's records have told us of "a vile act" that occurred

after he started back to England. The captain of the other

ship in the expedition, Thomas Hunt, tried slaving on his

own. He took seven Nauset Indians and twenty Patuxets, the

latter at future Plymouth, and sold them as slaves in Spain.

(Monks at Malaga later purchased the Indians their freedom.)

Although he was blacklisted from future employment in England,

Hunt's slaving brought retaliatory misery to later seafarers

coming to the New England coast. For the Pilgrims six years

later, it would bring difficulty and anxiety.

Ironically, though, Hunt's despicable behavior preserved

the life of an Indian vital to the Pilgrims, Squanto, later

described by Bradford as "a special instrument sent by God"

to help the new inhabitants. Squanto, also known as Tisquantum,

was among the Patuxets kidnaped by Hunt--and thus was saved

from the plague that would destroy all other members of his

tribe.

[The Divine setup continues, full force now.] In 1617 Capt.

Dermer, who had been on several voyages to the New World,

was in Newfoundland as Gorges' agent when he encountered Squanto,

who was trying to get back to his kin at Accomack (Plymouth).

Dermer at once saw an opportunity to help colonization. With

consenting Squanto, he headed back across the Atlantic to

Plymouth, England, to consult Gorges. [Had Squanto made it

back to Accomack at this time, he probably would have died

with the rest of his tribe in that plague.]

As Bradford would at a later date, Gorges saw Squanto as help

from Heaven. "It pleased God so to work for our encouragement

again," said Gorges, "as he sent into our hands Tisquantum...formerly

betrayed by this unworthy Hunt." Thus, said Gorges, "there

was hope conceived to work a peace between us and his friends,

they being the principal inhabitants of that coast..."

Gorges accordingly dispatched Dermer in 1619, along with Squanto,

to join others of Gorges' ships in New England. While most

of his men and boys fished off Monhegan Island, Dermer set

off on May 19 in a five-ton pinnace to explore the coast.

He took five or six crewmen with him, and Squanto as his guide.

"I passed alongst the coast where I found some ancient plantations,

not long since populous, now utterly void; in other places

a remnant remains, but not free of sickness. Their disease:

the plague, for we might perceive the sores of some that had

escaped, who described the spots of such as usually die,"

Dermer wrote to England.

Smith, telling of Dermer's experience and of the reports had

received--presumably from some of Dermer's crew--saw the effect

of the mysterious plague as an advantage to prospective planters.

"God," said Smith, "had laid this country open to us, and

slain most part of the inhabitants by cruel wars and a mortal

disease; for where I had seen 100 or 200 people there is scarce

10 to be found.

For Squanto, there were to be no kin to give him a homecoming.

When he and Dermer arrived at the seat of the Patuxet tribe,

where the Pilgrims would finally find asylum, they found "all

dead." Their cleared land, untended lands at the head of Plymouth

Harbor, as Smith suggested, awaited newcomers.

Of this place Dermer--who after wintering in Southern Virginia

made a second trip to future Plymouth just a few weeks before

Pilgrims left Delftshaven--wrote to Gorges: "I would

that the first plantation might here be seated."

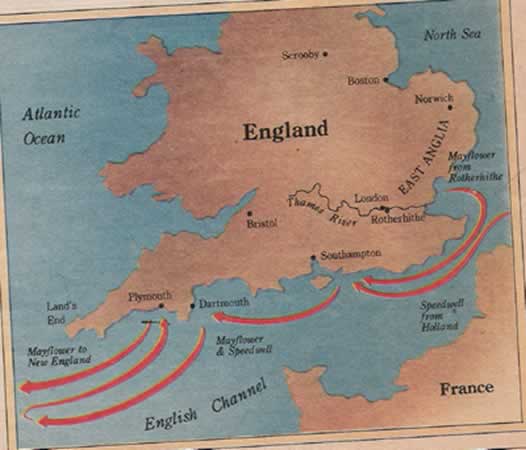

Below: A map of sailing routes

|