Chapter XI

A welcome peace treaty with Massasoit

It promises longterm security for their colony;

and Squanto's teaching, so crucial to the settlers,

points the way to eventual prosperity.

The surprise visitor,

an impressive figure of "seemly carriage," was Samoset, an

Algonquin sagamore (a chief) from Pemaquid Point in Maine.

The astounded Pilgrims did not invite him inside the common

house lest they reveal their limited numbers. It was a fair,

warm day, and they questioned him until night was coming,

for Samoset was the first native "we could meet withal." He

was "free in speech," though somewhat difficult to understand

because, said Bradford, he spoke "in broken English."

Samoset had learned the tongue from sailors who had been coming

for years to Monhegan Island, about 10 miles off Pemaquid

Point, to fish and trade. He had come to the Plymouth area

some eight months earlier with Capt. Thomas Dermer.

Accustomed to English ways, Samoset asked for some beer. The

Pilgrims had none, and instead gave him some "strong water

(liquer)...biscuit and butter and cheese and pudding and a

piece of mallard." And when the wind began to rise a little,

they solicitously "cast a horseman's coat about him."

Samoset had quite a bit to offer. He recounted the names of

ships, captains and mates who had visited Monhegan, and gave

details about the "east parts where he lived, which was afterwards

profitable to them." From Samoset the Pilgrims also, at last,

received information about their Indian neighbors, and about

this place where they were busy constructing their dwellings.

Its Indian name was Accomack and the clearings that had been

made for cornfields were those of the local Patuxet tribe,

whose members had perished in the plague four years past.

The nearest neighbors to the Pilgrims now were the Wampanoag

Indians, whose great sachem, Masssasoit, lived 40 miles away

at Sowams, in what is now Warren, R.I., on the Narragansett

Bay. Massasoit had 60 warriors, while the Nausets on Cape

Cod, who had escaped the plague, had 100--all "ill affected

towards the English" since the villainous Capt. Hunt, reviled

equally in England and the New World, kidnapped "20 (Patuxets)

out of this very place we inhabit and seven men from the Nausets...and

sold them for slaves."

As night came the Pilgrims, out of caution, would gladly have

had Samoset leave, but he wanted to stay the night. Ultimately

he was lodged with Stephen Hopkins, the only Pilgrim with

prior knowledge of Indians, whose house was directly across

Leyden street from Elder Brewster's.

With gifts of "a knife, a bracelet and a ring," Samoset departed

next morning, first making a promise that he would be back

again with other Indians and "with such beavers' skins as

they had to truck."

The Indians, of course, had quite naturally been watching

the newcomers, probably from the time they first dropped anchor

off the coast. Recently, as Bradford observed, the Indians

had been coming closer and even deliberately revealing their

presence. This wary reconnaissance was now approaching what

would be a very dramatic climax.

Samoset was back the next day, a Sunday, with "five other

tall, proper men." As the Pilgrims had instructed them, the

Indians left their bows and arrows a quarter mile from the

settlement. Some wore deerskins, some wildcat skins or fox

tails, and some "had their faces painted black, from forehead

to the chin, four or five fingers abroad."

"We gave them entertainment as we thought was fitting them,"

the Pilgrims reported in Mourt's Relation. "They

did eat liberally of our English victuals. They made semblence

unto us of friendship and amity." Indeed, they brought back

the tools that Capt. Standish missed the previous month in

the woods. And, said Mourt's, "they sang and danced

after their manner, like antics."

Samoset and his friends had brought along, as he had promised,

some beaver skins. But anxious as the Pilgrims were to initiate

trade, they still would not barter on the Sabbath. In fact,

because of Sabbath obligations, they were eager for the Indians

to depart. They did urge the Indians to come again and bring

more skins, "and we would truck for all." Each Indian was

given a gift--"some trifles"--but then it developed that Samoset

wanted to stay. The rest left.

Samoset was "either was sick or feigned himself so," said

the Pilgrims. The Indian, it would appear, was merely trying

to see what further he might learn about these Europeans.

He stayed the first days of the week, which were so fair and

warm that the Pilgrims dug ground and planted more garden

seed. These were British seed--wheat and beans--and some of

them, said Bradford, "came not to good," having become defective.

It was during this week, on March 21, that the Mayflower

voyage came finally to an end for the last of the passengers.

The carpenter, recovered from scurvy, completed some repairs

to the shallop and it went "to fetch all from aboard."

This day Samoset departed. The Pilgrims gave him some English

clothing--a hat, shoes, stockings and a shirt--and, showing

their anxiety to trade, asked him to learn from his companions

why they had not returned.

With Samoset gone, the Pilgrims once again resumed discussion

of their military organization. They had talked for only an

hour when they were again interrupted, this time by two or

three Indians--"daring us, as we thought"--who appeared on

Watson's Hill just across Town Brook. Capt. Standish and a

companion, with muskets, ran toward them. But as they drew

near the Indians "made show of defiance" and fled.

The next day--"a very fair, warm day"--would be one of the

most important in the entire life of the plantation.

Again the men assembled to discuss their public business.

[And amazingly enough, the Lord was about to show them that

the defense of their colony was to depend largely upon the

man whom he was about to bring to them.] And again, they had

scarcely an hour together when Samoset returned. With

him was the only remaining Patuxet, Squanto, one

of the Indians kidnapped by the notorious Capt. Hunt. Having

lived in England, Squanto, said Samoset, could speak better

English than himself.

The Indians had "some few skins to truck and some red herrings,

newly taken and dried, but not salted." They also had sensational

news: The great sagamore, Massasoit, was hard by,

with Quadequina, his brother, and all their men!"

Samoset and Squanto could not have been far ahead of the Indian

chief and his entourage--warriors and "their wives and their

women"--for hardly an hour passed before "the king came to

the top of the hill over against us, and had in his train

60 men, that we could well behold them, as they us."

The sight atop Watson's Hill was spectacular. Massasoit's

attire differed little from that of his warriors save that

he had "a great chain of white bone beads about his neck."

And, in Indian fashion, he was "oiled both head and face...All

his followers likewise were in their faces, in part or in

whole, painted, some black, some red, some yellow, and some

white...some had skins on them, and some naked; all strong,

tall men in appearance."

The Pilgrims, looking at the warrior array, could readily

see that the Indians outnumbered them nearly three to one.

For their part, the Pilgrims sought to be as impressive as

their resources would permit.

Both Pilgrims and Indians were wary. When neither group gave

a sign of sending its leader, Squanto went across the brook

and returned with the word of Massasoit desired that "we should

send one to parley with him."

The choice for this crucial diplomatic task was Edward Winslow--25

years of age, courageous, innovative, a future governor. Winslow

took gifts: a pair of knives and a copper chain with a jewel

in it for Massasoit; a knife and "a jewel to hang in his ear"

for Quadequina; and "a pot of strong water, a good quantity

of biscuit and some butter."

Though Pilgrim Winslow was hardly on speaking terms with the

king of England, he began his speech to Massasoit with the

assurance "that King James saluted him with words of love

and peace, and did accept of him as his friend and ally; and

that our governor desired to see him and to truck with him

and to confirm a peace with him as his next neighbor."

The Pilgrim food furnished a hilltop repast, with Massasoit

much taken by Winslow's sword and armor. Winslow then remained

as hostage with the sachem's brother while Massasoit and twenty

of his warriors crossed the brook. They did leave their bows

and arrows behind, though the sachem kept "in his bosom, hanging

in a string, a great long knife." Six or seven of the warriors

became hostages for Winslow.

Massasoit was met by Standish, an aide and six musketeers.

After an exchange of salutes, he was taken to a house then

being built in which the Pilgrims had placed a green rug and

three or four cushions for their visitor. Gov. Carver then

entered, to the sound of drum and trumpet. Behind him came

a few musketeers.

There were official salutations. Carver kissed Massasoit's

hand, Massasoit responded in kind, and they sat down. When

the governor called for strong water and drank to him, Massasoit

responded by taking "a draught that made him sweat all the

while after." They ate a little fresh meat; and thereupon

concluded a six-point treaty that the Pilgrims assured Massasoit

would make King James "esteem of him as his friend and ally."

The Pilgrims then conducted Massasoit back to the brook. There,

instead of receiving Winslow, they were greeted by Massasoit's

brother. Quadequina--"a very proper, tall young man of a very

modest and seemly countenance"--was also well entertained.

On Quadequina's return to the brook, the Indians released

their hostage.

The peace treaty was expressed in simple, direct terms:

Neither people was to harm the other. Each would punish their

own offenders against the other's people. If anything was

stolen, it would be returned. Each would aid the other in

the event "any did unjustly war against him." Each would seek

to have the other's "neighbor confederates" join in the treaty.

Each would leave any weapons at a distance when making visits.

That night Massasoit and his men camped in the woods a half

mile away. Only Samoset and Squanto stayed with the Pilgrims,

"who kept good watch" but found "no appearance of danger."

Massasoit and his people departed the next morning, leaving

behind a promise that they would come again.

The treaty, now mutually confirmed, offered a prospect

of peace and security for the religious haven the Pilgrims

were creating. In fact, the Pilgrims felt that the treaty

could be decisive as to whether or not the plantation would

have a future here at all. And as it turned out, the agreement

made possible the fulfillment of other pressing needs of the

settlers: an adequate food supply, and development of the

trade that would permit the Pilgrims to free themselves from

Old World debts.

At the moment, though, the Pilgrims had no way of knowing

whether this far-reaching treaty would last. Massasoit had

hardly taken his leave, after giving some ground nuts and

tobacco to Standish and Isaac Allerton, when the Pilgrims

started speculating on the chief's motivation for making the

treaty.

They could not "conceive but that he is willing to have peace

with us," because Indians had had numerous opportunities to

injure Pilgrims working or fowling in the woods and yet had

"offered them no harm." The Pilgrims had also observed that

Massasoit "trembled for fear" while the governor, and that

of his brother had made "signs of dislike" until the Pilgrims'

weaponry was removed. "Our pieces," they noted, "are terrible

unto them."

ABOVE ALL, THE PILGRIMS HAD

LEARNED OF AN Indian menace confronting Massasoit. It came

from the powerful tribe that lived on the west side of Narragansett

Bay--a tribe that had sustained no losses from the dreadful

pestilence back in 1616-1617. Massasoit, concluded the Pilgrims,

"hath a potent adversary, the Narragansetts, that are at war

with him, against whom he thinks we may be some strength to

him." They would be--and very soon.

That Friday, March 23, Squanto, following up on his vital

contribution as interpreter-diplomat during Massasoit's visit,

launched on his role as instructor to the Pilgrims--a service

that would lead a grateful Bradford to describe Squanto as

"a special instrument sent by God for their good beyond their

expectation." That spring, said Bradford, Squanto "directed

them how to set their corn, where to take fish, and to procure

other commodities, and was also their pilot to bring them

to unknown places for their profit, and never left them till

he died."

Right after Massasoit departed, Squanto showed the Pilgrims

how to catch eels. Presumably he went to a stream just

south of Plymouth Harbor, the one now called Eel River. "He

trod them out with his feet, and so caught them with his hands,

without any other instrument." The eels were "fat and sweet"

and everyone felt glad when Squanto came back that night "with

as many as he could well lift in one hand."

Meanwhile Standish, in the meeting so often interrupted, finally

completed the Pilgrims' military arrangements. With March

25, their New Year's Day, only two days away, the Pilgrims

held an election, and again chose John Carver as governor.

Carver, like Brewster, was in his mid-50's. He was the oldest

of the surviving Pilgrims--and he had but a few weeks of life

remaining.

Some laws were also adopted that Friday, and they were most

timely. Shortly thereafter a lawful order of Standish brought

a torrent of abuse from one Londoner, John Billington, a man

of violent nature. As punishment he had "his neck and heels

tied together." His humble plea for pardon brought this first

offender in the colony a quick, compassionate release--but

produced no reform in him.

April 5 was finally chosen as the day the Mayflower was

to begin its return voyage. As the day came there was not

a single Pilgrim--despite the suffering, hardship and death

that had been their lot since coming to the New World--who

gave the slightest sign of wishing to go back with the surviving

crew.

Bradford went to unusual lengths in explaining the ship's

delayed departure: "The reason on their (the Pilgrims') part

why she stayed so long, was the necessity and danger that

lay upon them; for it was well towards the end of December

before she could land anything here, or they able to receive

anything ashore. Afterwards, the 14th of January, the house

which they had made for a general rendezvous by casualty fell

afire, and some were fain to retire aboard for shelter; then

the sickness began to fall sore amongst them, and the weather

so bad as they could not make much sooner any dispatch.

"Again the Governor and chief among them, seeing so many die

and fall down sick daily, thought it no wisdom to send away

the ship, their condition considered and the danger they stood

in from the Indians, till they could procure some shelter;

and therefore thought it better to draw some more charge (debt)

upon themselves and friends than hazard all.

"The master and the seamen likewise, though before they hasted

the passengers ashore to be gone, now many of their men being

dead...and the rest many lay sick and weak; the master durst

not put to sea till he saw his men begin to recover, and the

heart of the winter over."

For Master Jones, the Mayflower's return voyage would

be his last. Like so many of his crew, he might have "taken

the original" of his death in the exposure and strain that

contributed to the General Sickness. The Mayflower reached

London in roughly a month, May 6, a quick passage. But in

just a few months more Jones' widow and their two young children

buried him in the churchyard in Rotherhithe, on the south

bank of the Thames River. [It goes without saying, but I'll

say it. We owe Master Jones a special debt of gratitude for

all he did, which ultimately cost him his life.]

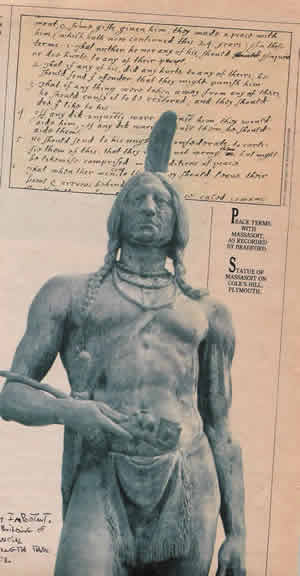

Massasoit-PeaceTreaty

Massasoit & Gov. Carver Make Peace Agreement

|