IV. Oceanic Biology 101

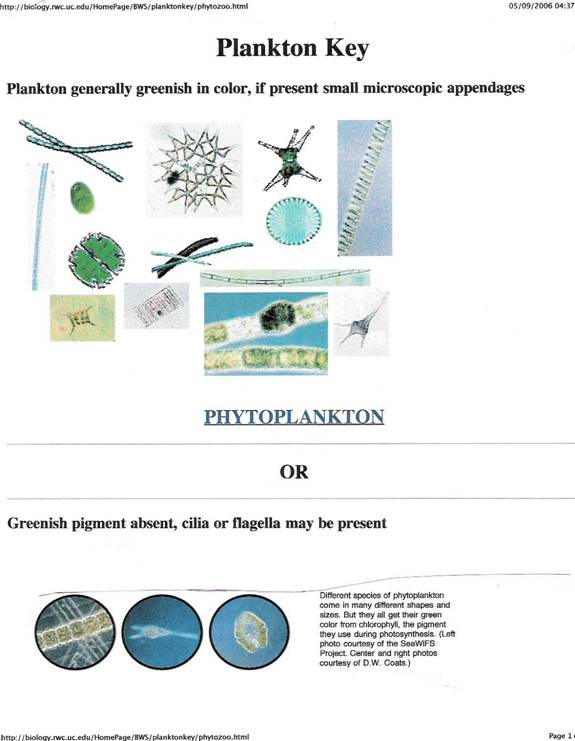

Phytoplankton grow abundantly in oceans around the world, and they

exert a worldwide influence on the world’s climate. That is why phytoplankton are on the top of

the list for oceanographers and Earth scientists for study around the

world. Phytoplankton require

the same basic ingredients land plants do, sunlight, water, and nutrients. C02 is one of those ingredients. Because sunlight is strongest near the surface

of the sea phytoplankton remain either at the surface or near it. They contain chlorophyll, which makes them green. It is used for photosynthesis, converting C02 and water into

sugars, carbohydrates, i.e. plant food. They also require iron and other nutrients to

survive. When surface waters

are cold, the deeper waters are allowed to rise, bringing nutrients

upward to the surface. This stimulates

rapid phytoplankton growth. When

surface waters are warm, this upwelling is prevented, and the phytoplankton

population drops, as they starve. Individual

phytoplankton live only a couple

days at the most, so when they die on a regular basis, each one sinks

to the bottom. Over long steady

periods of time the ocean has proven to be a huge sink for atmospheric

carbon dioxide. About 90 percent of the world’s total carbon

content has settled to the bottom of the ocean, mainly in the form of

biomass from these dying phytoplankton. Another form of carbon storage is via the steady deposits of

CaC03, calcium carbonate, which we will look at soon. Phytoplankton use carbon dioxide for photosynthesis. The larger the world’s phytoplankton population,

the more C02 is pulled from the atmosphere and locked on the ocean’s

floor. Any given population of

phytoplankton can double its population on the order of once a day—if

the conditions are right. They

respond to conditions in their environment very rapidly. The health of the oceans is essential for this natural C02 scrubber

to work at peak efficiency. [For a full description see http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Library/Phytoplankton/ ]

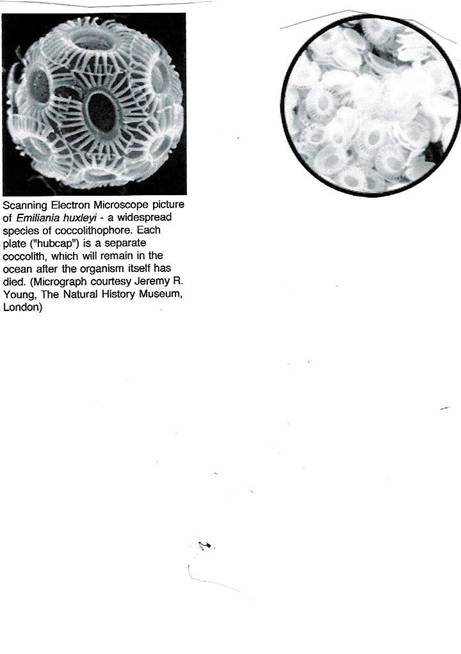

Coccolithophores: Coccolithophores are a type of phytoplankton that

do not require rich nutrients to survive and reproduce, but flourish

in warmer, nutrient poor seas. They

live mainly in subpolar regions. They

are one-celled marine plants that live in large numbers in the upper

layers of the oceans. They have

a very unique makeup. They, through

their unique body chemistry, surround themselves with microscopic “plating”

made of CaC03, calcite, or commonly known as limestone. These plates resemble hubcaps and measure about three one-thousandths

of a millimeter in diameter. They

can have up to thirty of these “hubcaps” attached to their round bodies. These hubcaps are called coccoliths. As additional coccoliths are formed, the excess

ones drop into the water, sinking to the bottom. Also when a coccolithophore dies, it sinks along

with all its hubcaps of CaC03. In

areas of trillions of these one-celled C02 scrubbers, the water will

turn opaque turquoise from dense clouds of them. Scientists estimate that these organisms dump more than 1.5 million

tons of calcite (CaC03) onto the ocean floors every year. [see http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Library/Coccolithophores/ and http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Library/Coccolithophores/coccolith_3.html ] Coccolithophores’ short-term

effect on the environment is a little more complex. The chemical reaction to form the coccoliths, in locking away

a C02 molecule into one molecule of CaC03, releases one molecule of

C02 back into the water and/or atmosphere. But as a plant cell, it is also absorbing C02 in photosynthesis. So this effect must be minimal, and the coccoliths

constant falling to the sea-floor provides a constant scrubbing of C02. Also the color of these one-celled hubcap phytoplankton is reflective

to sunlight, helping lower the surface temperature of the ocean where

they are proliferating. [see also http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Study/Coccoliths/bering_sea.html and http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Study/Coccoliths/bering_sea_2.html and http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Study/Coccoliths/bering_sea_3.html and http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Study/Coccoliths/bering_sea_4.html for a full treatment of this subject.]

V. Ocean & Atmosphere, How They Interface

The Problem With Computer Models: Computer

models (and climatic modeling has been going on since the late 1960’s)

show that when a certain specific rise in C02 levels are plugged into

them, there will be a specific projected or calculated rise in ocean

surface temperature in these models. The real problem is this. Since the start of the Industrial Revolution

(1750), there has been a whopping 31 percent rise in carbon dioxide,

C02 levels in the Earth’s atmosphere. But ocean surface temperatures have NOT risen as much as the computer models show that they

should have. Why? The answer is basic. We used to have a saying

for computers, and this applies to computer models as well: Garbage in, garbage out. Now

wait a minute. In no way am I

saying that all these brilliant Earth, Oceanographic, Glaciologist and

Meteorological scientists are putting “garbage” into their computer

models. Far from it. The issue is with the complexity of the actual formula that drives

Earth’s climate and ocean temperatures. They haven’t been dealt with a full pack of cards, knowledge

cards, so to speak. Scientists

rely on information they can readily discern through direct (and indirect)

observation. They simply haven’t plugged into their computer

models all the facts. As satellite

observations get more and more sophisticated, and Nomad buoys do a better

and better job of monitoring ocean temps, and probes do the same for

shallow and deep ocean currents, the models will get increasingly more

accurate. So the interplay between

ocean and atmosphere is far more complex than it appears to be. Greenhouse gases are not the only things that

influence global temperatures. There

are many ingredients in this complex equation. Energy and chemicals make up the basic “programming language”

of atmospheric and ocean climate. Greenhouse

gases provide some of the chemical “programs” and the energy, obviously,

is the sun. There is a constant

“talk” through these variable “program languages” between atmosphere

and the oceans. Clouds and ice

sheets also provide huge variables in how much of the suns energy is

reflected back into outer-space and how much is absorbed into the Earth’s

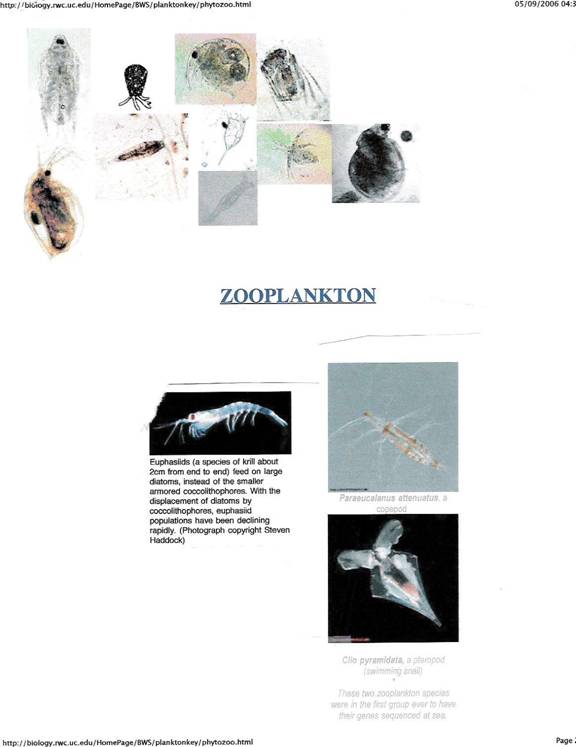

climate (atmosphere, oceans and land). Even plankton, with its varying color it lends to the ocean surface

changes its solar reflective or absorptive ability—with green plankton

increasing the absorptive qualities and Coccolithophores reflective

white color making the oceans more reflective to solar energy (infrared,

heat spectrum). Desertification,

exposing the earth to expanding sandy deserts (such as the moving of

the Sahara into the region of the Sahel makes the Earth reflective,

amazingly, but forestation increases absorption. But trees at the same time are giant evaporators,

and thus air-condition the ground

and air beneath them (energy absorbed in evaporation of water through

their leaves and pine needles cools them and the surrounding air. That’s why forests are cooler than open fields. Even the black tar of our roads and highways must be plugged

into the formula, as does the color of your roof on your house! Satellite mapping of the precise coloring of the earth, down

to very small areas is now possible, and computers are powerful enough

to handle this great amount of data. It is merely a matter of time before the scientists,

who tend more and more to work together on these projects and models,

program enough data into their models to make them very accurate. But what

scientists have found in recent decades is that the world’s oceans have

partially offset the anticipated global warming due to greenhouse gas

levels by exerting a cooling effect on climate by nature of their very

size, mass and volume. The Big Worry is this—over the long

run (who knows how long that will be—Russian roulette anyone?), “scientists

don’t know whether the ocean’s cooling influence will persist.” So says David Herring of EarthObservatory.nasa.gov. Are we willing to gamble? As

the Industrial World strives to put the brakes on its’ C02 emissions

(which will take multiple decades to achieve [i.e. transforming of all

automobiles to first hybrid, and then straight electric/solar, all power

companies either nuclear, wind, or solar—we’re talking a 100 year minimum]),

on the other hand huge major nations which used to be thought of as

3rd world are striving with all their might to industrialize—with

no constraints in place to limit C02 emissions to industrialize. China and India are the two biggies. China is firing up one coal-fired power plant after another in

rapid succession. Many smaller 3rd world nations can

be added to this list as well, increasing the overall C02 output beyond

our capabilities to curb. Even if all the industrialized nations came

under the Kyoto Accords, and met its standard immediately it would not

be enough to stop the rise in C02 levels. And the Chinese and Indian

populations are fast becoming owners and operators of automobiles. The big question is, before we “get

our collective global act together”—will the atmosphere and oceans reach

some sort of “trip point” which makes global warming irreversible until

its side effects have wreaked worldwide disaster—on a global scale? [ http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Library/OceanClimate/ and http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Observatory/Datasets/cldfrc.isccp_c2.html ] [See

also http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2000/01/000131080830.htm ]

|